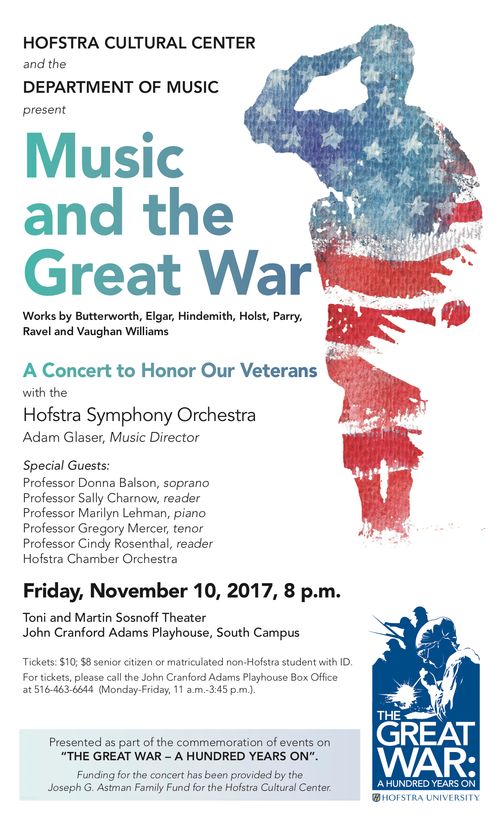

Music and the Great War:

A Concert to Honor Our Veterans

Hofstra University, November 10, 2017

Notes on the Program

by Adam Glaser

As Hofstra University is marking the centenary of World War I, and in honor of Veterans Day, the Hofstra Symphony Orchestra and our special guest artists are proud to present “Music and the Great War,” a concert of works by selected composers and writers whose personal journeys were intertwined with this major world event. The majority of works on the program are by early 20th-century European artists whose lives were directly impacted by the Great War, including several who actually served in it. Some works played a galvanizing role during the war itself, while others preceded the Great War but would evolve into cherished anthems during and/or beyond it. Gustav Holst’s riveting “Mars, The Bringer of War” from The Planets was written just before the outbreak of WWI, and yet its encapsulation of wartime horrors would prove to be both timely and prescient. Still other works on this program have little or even nothing to do with the Great War, but are revealed as prime examples of the musical genius that was nearly – or in some cases, completely – lost on the battlefields. In all cases, these musical treasures might serve to remind us of a simple, deeply encouraging truth: one person’s contribution can make a world of difference.

* * *

“The Star-Spangled Banner” actually has its initial roots in England, where the British composer John Stafford Smith (1750 – 1836) wrote the tune to a poem by Ralph Tomlinson, “To Anacreon in Heaven.” The melody made its way into other iterations across the Atlantic before attorney Francis Scott Key (1779-1843) penned his famous lyrics following the 1814 bombardment of Fort McHenry. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed an executive order designating it as the “national anthem” for military ceremonies, and in 1931 Congress would formally designate “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the United States’ national anthem.

British composer Gustav Holst (1874 – 1934) composed “Mars, The Bringer of War” to open his orchestral suite, The Planets, in 1914, its menacing harmonies and driving rhythms seeming to foreshadow the horrors just around the corner. Holst employs large sections of woodwinds, brass and percussion, using these forces to highly dramatic effect throughout the movement. While Holst’s attempts to enlist in the British armed forces were unsuccessful, he would ultimately take a position with the YMCA to arrange concerts for British soldiers in Greece and Turkey toward the end of the war.

British composer George Butterworth’s (1885 – 1916) The Banks of Green Willow makes us wonder just how much beautiful music the world may have lost when this 31-year-old soldier died in 1916’s Battle of the Somme. Written just three years earlier in 1913, this short “idyll for small orchestra” incorporates two folk songs, “The Banks of Green Willow” and “Green Bushes,” a practice shared by his collaborator Ralph Vaughan Williams, as we will hear later in the concert. Featuring lyrical solos from several corners of the orchestra, the piece weaves a delicate tapestry of melodies to evoke pastoral beauty, a stark contrast to the horrors the composer would witness just a few years later. As described by ClassicFM.com, “it has become almost a symbol of that long-lost halcyon Edwardian age, as if Butterworth were transcribing the disappearing world around him.”

Writer Edmond Fleg (1874 – 1963) was born in Geneva, Switzerland, ultimately moving to France in 1892 and joining the French Foreign Legion during World War I. While he has direct ties to the music world, having written the librettos for Ernest Bloch’s opera Macbeth (1910) and George Enescu’s Oedipe (1936), his contribution to tonight’s program is an excerpt from his poem Wall of Weeping, written in 1919, which touches upon WWI, the Wailing Wall and his Jewish identity.

The Great War’s impact on the life of French composer Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937) is multi-layered. Ravel’s physical condition hindered his options for service; his light body weight did not meet the minimum to serve in the infantry, and he was rejected from the Air Force due to poor health. Still, he continued to search for ways to serve: caring for wounded soldiers, driving trucks for the military supply department, transporting supplies, and rescuing abandoned trucks in battle.

One can argue that Ravel’s service continued after the war through his music, notably in the 1930 composition of his Piano Concerto for the Left Hand for Paul Wittgenstein, an Austrian soldier and pianist who had lost his right arm in the war. After his six movement piano suite, Le tombeau de Couperin, was composed between 1914 and 1917, Ravel would dedicate each movement to one of six friends who had lost their lives in the Great War, including Jean Dreyfus, who is memorialized in the beautiful, perhaps bittersweet “Menuet.”

Just before the start of the Great War in 1914, Ravel was commissioned by singer Alvina Alvi to compose Deux Mélodies Hébraïques (Two Hebrew Melodies). The first melody is the “Kaddisch” which appears in Jewish prayer books and is spoken by those who have lost family or loved ones (also known as the “Mourner’s Kaddisch”). The second melody, “The Eternal Enigma,” is based on a Yiddish verse and leaves questions about the world completely unanswered. Like Holst’s “Mars,” this pair of pre-war melodies would take on added significance in the years following their composition.

Composed in 1909, Gustav Holst’s Suite in E-flat was originally scored by the composer for wind band, and has become a masterwork in its own right. Tonight’s program features an arrangement for orchestra by the British composer Gordon Jacob (1895 – 1984), who was captured as a prisoner of war in 1917. While in captivity, Jacob would come across old instruments and books in the POW camps, using them to study composition. Importantly, he would also find kindred spirits in other prisoners who loved and played music.

This highly profound theme – music as a source of solace during tragic events – would find many iterations on both sides of the conflict. German composer Paul Hindemith (1895 – 1963), an accomplished violinist who served as the concertmaster of the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra, left the orchestra from 1917 to 1918 to serve in the army, playing in a military band and a string quartet. While performing the Debussy String Quartet for his commanding officer, the concert was interrupted by a report that Debussy had died. Hindemith recalled the poignancy of that moment:

It was as if the spirit had been removed from our playing. But now we felt for the first time how much more music is than just style, technique and an expression of personal feeling. Here music transcended all political barriers, national hatred and the horrors of war. Never before or since have I felt so clearly in which direction music must be made to go.

Hindemith would emigrate from Germany to Switzerland just before the outbreak of World War II, soon after finding his way to America where he taught at Yale University from 1940 to 1953. Our selections from his Five Pieces for String Orchestra, Op. 44, No. 4, written in 1927, reveal this master composer’s penchant for modern tonalities, creative development of melodic motifs, and highly dramatic use of dynamics and phrasing.

Ralph Vaughan Williams’ (1872 – 1958) keen interest in folk tunes fueled the creation of two works on our program: his Fantasia on Greensleeves, arranged by Ralph Greeves from the opera Sir John in Love, and his English Folk Song Suite, arranged for orchestra by Gordon Jacob. The Fantasia actually includes two folk tunes -- the famous “Greensleeves,” and another tune, “Lovely Joan” – while the English Folk Song Suite, here orchestrated by Gordon Jacob, includes nine folk tunes, among them “Green Bushes” in the second movement, which we also heard in Butterworth’s The Banks of Green Willow.

British poet Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967) used brutal imagery and detail to evoke the horrors of the Great War. His poem, “A Working Party” was written while on the front lines from the trenches. It briskly paints a vivid picture of a soldier’s death, rendering the scene, the story and the soldier himself with poignant immediacy.

While our focus is primarily on the music of European composers, tonight’s program includes a meditation American composer George M. Cohan’s (1878 – 1942) signature contribution, “Over There.” One of the most successful hit records of its time, Cohan’s song would serve to rally the American public around the war effort across the Atlantic, with a catchy, rousing chorus:

Over there, over there

Send the word, send the word over there

That the Yanks are coming, the Yanks are coming

The drums are rum-tumming everywhere

So prepare, say a prayer

Send the word, send the word to beware

We'll be over there, we're coming over

And we won't come back till it's over over there.

Composed by Cohan after learning that the United States entered the conflict in 1917, “Over There” would spawn numerous interpretations in the decades that followed.

While the last three works on our program contain melodies that were closely bound to nationalistic pride, this was not necessarily by design. Edward Elgar’s (1857 – 1934) masterpiece, the Enigma Variations, is a collection of short musical tributes to various friends in his life. The ninth among these is the beautiful “Nimrod” variation which was dedicated to his friend August Jaeger, but would evolve into something of much greater significance throughout 20th-century British history. Author Julian Rushton writes: “Through irreversible processes of association, ‘Nimrod’ has acquired an independent life as a national elegy.” Rushton goes further to suggest that it is “now as much part of the musical representation of England (sometimes Britain) as the trio of the first Pomp and Circumstance March and the tune in Holst’s Jupiter.”

Unlike the “Nimrod” variation, the rousing “Jerusalem” by British composer Hubert Parry (1848 – 1918) was composed intentionally as a patriotic gift to England. Parry set William Blake’s poem, “And did those feet in ancient times” to music in 1916 at the suggestion of poet laureate Robert Bridges. “Jerusalem” was premiered at a meeting of Fight for Right, a movement formed the previous year in an effort to galvanize British support during the Great War. Its special significance has endured well beyond WWI.

First appearing as the fourth movement of Gustav Holst’s The Planets suite, “Jupiter, The Bringer of Jollity” has become an audience favorite on its own with its brilliant orchestration, a colorful use of the pentatonic scale, and an exceptionally beautiful middle theme that would become the British patriotic hymn, “I Vow to Thee My Country.” There is something about Holst’s The Planets that is rather (wait for it) universal, and the melodies in “Jupiter” are no exception, stirring emotions in the hearts of listeners around the world.

* * *

Tonight’s roster of composers impacted by the Great War is far from complete, omitting such major European luminaries as Arnold Schönberg, Alban Berg, Anton Webern and Enrique Granados, to name a few. While the influence of the war on American composers was relatively limited compared to those in Europe, there is certainly a significant amount of American music and poetry colored by these events. Looking back at the Great War through a musical lens, we are only examining one microscopic slice of an overwhelmingly complicated event. Still, even a small cross-section reveals the enormous influence this watershed moment in world history would have on the lives and works of so many important figures in music history.

Download the complete Music and the Great War concert program here.